Simon

Bolivar (SEE-mohn boh-LEE-vahr) was one of the most powerful figures in

world political history, leading the independence movement for six nations

(an area the size of modern Europe), with a personal story that is the

stuff of dramatic fiction. Yet today outside of Latin America, where he is

still practically worshipped, his name is almost unknown.

Born to

wealthy Creoles in Caracas, Venezuela, on July 24, 1783, his father died

when he was three and his mother six years later. Simon was reared by an

uncle with a tutor who exposed him to the writers of the Enlightenment,

such as Voltaire and Rousseau, who were inspirations for the French

Revolution. The tutor, Simon Rodriguez, fled the country when he was

suspected of conspiring to overthrow Spain's colonial rule in 1796.1

At 16, Bolivar

was sent to Spain to complete his education and on the way, his ship

stopped in Vera Cruz. During an audience with the viceroy, he audaciously

praised the French Revolution and American independence, both of which

made Spanish officials nervous.2

In 1802, he

married the daughter of a nobleman in Spain and returned to Caracas, only

to have her die a year later from yellow fever. As a way of keeping his

mind off of his grief, Bolivar decided to return to Europe to immerse

himself in the intellectual and political world he had found so

stimulating.3

While in

Paris, he met Alexander von Humboldt, the great naturalist who had just

returned after five years in South America. As von Humboldt spoke of the

enormous natural resources and wonders of the continent, Bolivar remarked,

"In truth, what a brilliant fate--that of the New World, if only its

people were freed of their yoke."

Von Humboldt

responded, "I believe that your country is ready for its

independence. But I can not see the man who is to achieve it." It was

a fateful comment Bolivar was to vividly recall the rest of his life.4

Naturalist Alexander von

Humboldt in Ecuador, 1806.

He also

witnessed the coronation of Napoleon as emperor on December 2, 1804.

Bolivar was appalled at what he felt was a betrayal of the principles of

the Revolution, yet he took note of the ability of one man to change the

course of history.5

Bolivar had

met up with his old tutor, Rodriguez, and the two traveled to Rome, where

they again crossed paths with von Humboldt. On August 15, 1805, Bolivar

found himself with Rodriguez on Monte Sacro (Aventine Hill), a place

associated in Roman history with freedom from oppression. The 22-year-old

feel to his knees and, grasping his teacher's hands, vowed to free his

country. After returning to Paris, Bolivar sailed for America, stopping

often along the east coast before arriving home in 1807.6

The following

year, France invaded Spain. By 1810, the city council of Caracas had grown

bold enough to depose the Spanish viceroy and sent Bolivar to London to

seek protection from the British government against any attempt by France

to seize Venezuela.7 No help was forthcoming, but Bolivar recruited

Francisco de Miranda, who had spearheaded a prior revolt, to return to

head the new independence movement.8 While in London, Bolivar also

had his most famous portrait painted. On close examination, a medallion

hanging from his neck reads, "There is no fatherland without

freedom."9 When he left on September 21, he was never to

return to Europe.10

Portrait of Francisco

de Miranda

As is typical

of revolutions before history is rewritten to present all the natives as

patriots, what followed in South America was as much civil war as an

effort to throw off the colonial yoke. The see-saw power struggle between

revolutionary and loyalist factions and with the royal forces was to last

14 years (followed by several years of occasional conflict between

factions in the liberated territories).

In March 1811,

a national congress met in Caracas. Though not a delegate, Bolivar gave

his first public speech to the group, saying, "Let us lay the

cornerstone of American freedom without fear. To hesitate is to

perish." The First Republic was declared July 5, Venezuela becoming

the first colony anywhere in the Spanish empire to attempt to break free.11

Like many in

the aristocracy, Bolivar had slaves, and in the spirit and excitement of

the independence movement he was the first to set them free. 12 He

was later to call for the abolition of slavery across the entire Western

Hemisphere.13

Although he

had no formal military training and no battlefield experience, Bolivar was

made Lieutenant Colonel serving under Miranda. He participated in his

first engagement on July 19, an assault on the Spanish stronghold of

Valencia in which he distinguished himself, but the rebel forces were

repelled. A siege forced capitulation on August 19th after

heavy losses on both sides. It was a harbinger of things to come.14

Miranda and

Bolivar had been having an increasing number of serious disagreements,

from how to treat counterrevolutionary conspirators (Bolivar was for

execution) to whether those born in Spain should be allowed to stay

(Bolivar wanted them expelled). Meanwhile, on the political front the

republicans were suffering from lack of governing experience. Within a few

months, the captured royal treasury was spent and a Spanish blockade led

to a worsening economic situation.15

On March 26,

1812, two years to the day after the Caracas city council had deposed the

viceroy, a severe earthquake hit the region, killing 10,000. Areas where

loyalists to Spain resided were little affected and religious hysteria

followed, blaming the independence movement for defying God's chosen

monarch. The Spanish commander-in- chief, Juan Domingo de Monteverde, took

advantage of the situation, marching out into the country, even finding

rebel units eager to switch sides. However, Miranda, who had 5,000 men vs.

Monteverde's 3,000, could have struck a decisive blow if he had gone on

the offensive instead of being overly cautious. In the few times they

clashed, Miranda held back his men from pursuit which could have

annihilated the Spanish.16

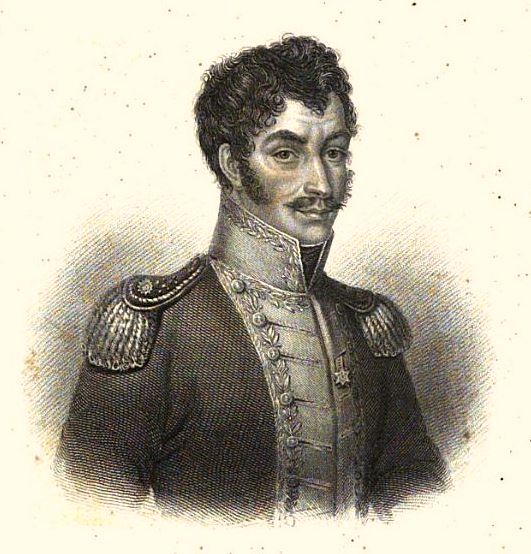

Portrait of Simon Bolivar, Published in 1837

Bolivar was

put in charge of the most important republican port, Puerto Cabello, where

a large number of prisoners were kept at the main fort, as well as a large

stockpile of arms and artillery (which played little role by either side

in South America's fight for freedom) . The combination proved fatal: a

traitor freed the prisoners who armed themselves and began bombarding

Bolivar's position. He and his men barely escaped with their lives.17

Bolivar felt

disgraced by the loss and furious that Miranda had not responded to calls

for help. Shortly thereafter, he and other officers turned Miranda over to

the Spaniards.18

As the Spanish

completed their reconquest of the country, Bolivar escaped to Cartagena in

New Granada (now Colombia), where rebels held power (though locked in

civil war with a rival faction in Bogata).19

There in 1812,

he wrote the first of his many eloquent political manifestos, saying,

"Not the Spanish, but our own disunity led us back into slavery. A

strong government could have changed everything." He began

championing a political system in which the nobility played a strong role,

led by a president for life. He condemned the leniency against crime in

general and against the state in particular that he felt had contributed

to the fall of the First Republic. He began arguing that Venezuela should

be liberated as the first step in creating an entire continent of

independent states.20

The government

of New Granada authorized a revolutionary force to liberate the

Spanish-held bastions in their territory and in Venezuela, headed by

Pierre Labatut. Against orders, Bolivar took 200 of the men and boldly

attacked a Spanish garrison, capturing supplies and boats. One small

victory followed another and the rebel ranks swelled.21

As a result of

his actions, Bolivar was named commander-in-chief of the entire New

Granadian army.22 He had to improvise tactics as he went along,

finding European tactics he read about in books useless in a land of

enormous mountain ranges, deep gorges, rushing rivers, vast plains, no

roads, minimal ability to communicate over any distance, and sparse

population.

Taking 650

men, he reentered Venezuela in May 1813. Facing 4,000 Spanish soldiers,

Bolivar's expedition seemed foolhardy. Using speed and surprise, he would

defeat units of the Spanish army and the population rose up to swell the

ranks of the republicans. He also recruited from the enemy by offering

amnesty for deserters, threatening to kill captured Spaniards. Though only

occasionally carried out, he believed that only through such a drastic

measure could the republicans win and avoid the slaughter and plunder of

civilians that was inevitable if they lost.23

After five

swift victories, Bolivar had built up an army of 2,500, which came across

1,200 of the enemy, who retreated swiftly towards Valencia. He placed two

men on each of 200 horses and had them ride around the Spanish through the

night. The Spanish found their way blocked in the early morning of July 31

and in the Battle of Taguanes the revolutionaries crushed the royalists.

It was Bolivar's first large-scale victory (by the small-scale standards

of South American war).24

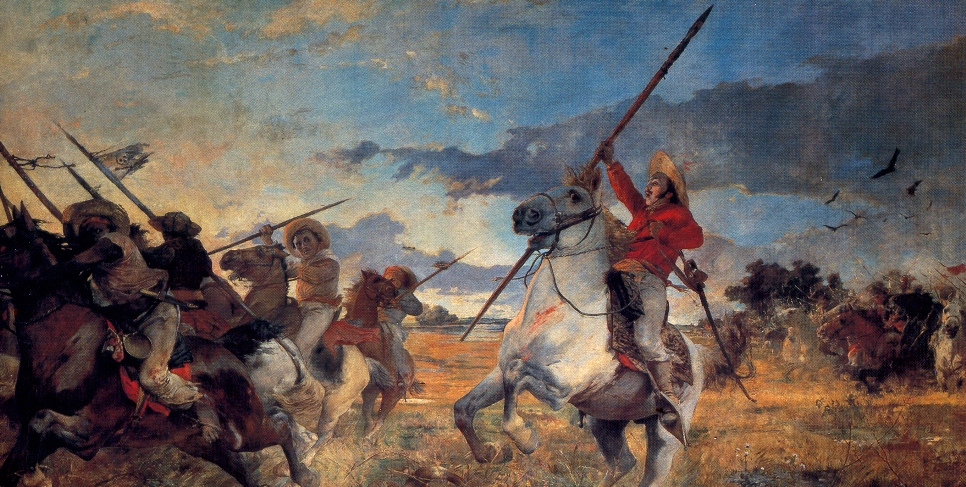

The Battle of Taguanes

The republican

army reentered Caracas on August 7, where Bolivar, now 30, was given

dictatorial powers, although half of Venezuela remained under control of

the crown, which had 10 times the number of troops, who were, of course,

much better equipped and trained.25

Gradually, the

population grew war-weary and sentiment turned against the independence

movement, which was also hindered by being poorly equipped (the infantry

typically had antiquated muskets which required six motions to load; often

running out of ammunition, they resorted to bayonet attacks, when they had

bayonets).26

The Spanish

leaders also began recruiting the fierce llaneros, nomadic

cattle-raising horsemen of the Amazon grasslands. They appointed Jose

Tomas Boves, a former rebel embittered by having been imprisoned by his

comrades, to head them. Known as the Legion of Hell, it consisted of as

many as 10,000 riders using spears, knives, and bolos, easily superior to

better-armed republicans, who were almost entirely infantry. They began

waging an even more savage war, so the rebels responded in kind, even

killing civilians who would not take up arms against the royalists.

Prisoners were executed on the spot. There was no grand war strategy, no

static fronts, just one pitched battle after another between a few hundred

or few thousand.27

On November

10, Bolivar inflicted what seemed to be a defeat on the llaneros

and Spanish soldiers at Barquisemeto, but in the midst of the pursuit by

the republicans, someone in their camped issued a call to retreat,

throwing the army into confusion and the roles were reversed, the Spanish

turning to pursue. It was Bolivar's first personal battlefield loss in

one-and-a-half years. The first regiment to retreat was stripped of its

medals, rank, and banners.28

Then on

December 5, at dawn, Bolivar's 3,000 attacked 5,000 Spanish forces under

General Monteverde, who were on in the hills near Araure. The patriot's

advance unit was immediately wiped out, but while Monteverde was

reinforcing his flanks where he expected the next assault, rebels armed

mostly with knives and sticks overran the center. After fierce

hand-to-hand combat, Bolivar himself led the charge which scattered the

Spanish. He gave chase until 2 a.m. the next morning, directing his men to

kill even those who surrendered.29

Over the next

few months, the patriots found themselves fighting on so many fronts that

they sometimes faced 7-to-1 odds. Bolivar's forces were nearly annihilated

several times.30

By February

1814, Bolivar had recruited some replacements and had dug in at San Mateo.

The Spanish, who had 10 times the cavalry, made repeated attacks on his

positions and nearly succeeded in overrunning them. At one point, they

almost captured the supply and munitions depot, until the defenders blew

themselves up to prevent its capture. The Spanish finally gave up after

several months.31

On May 28,

Bolivar's 5,000 faced 1,000 entrenched royalists in hills above the Plains

of Carabobo. Although his men were poorly armed, he knew that llaneros

were on the way to reinforce the enemy, so he decided to risk everything

again. The assault was so relentless that the Spanish fled.32

Batalla de Carabobo by Martín Tovar y Tovar

But with his

men nearly naked and the rainy season turning the region into a swamp,

Bolivar found it increasingly difficult to follow up, final victory always

slipping from his hands. On June 15, he gathered 3,000 soldiers at La

Puerta against Boves' equal number, and this time the revolutionaries were

trounced, Bolivar barely escaping from the field. As Boves marched onto

Caracas with his numbers increasing by the day, 20,000 fled the city.33

At Aragua,

Boves caught up with remnants of the patriot army and 4,000 men, mostly

Bolivar's, died in one of the bloodiest battles of the South American war

for independence.34

Bolivar

shipped 24 chests of church silver and gems to a safe point to buy arms

from British colonies and in September sailed to Cartagena.35 The

royalists gained control of Venezuela by the end of the year, reinforced

in May 1815 by 11,000 veterans of the Napoleonic wars, the biggest

expedition the Spanish had ever sent to the Americas.36

Ever the

optimist, Bolivar wrote his fellow citizens, "I have been chosen by

fate to break your chains…Fight and you shall win. For God grants

victory to perseverance." He exhorted his men that misfortune was the

"school of heroes."37

The government

of New Granada gave him an army to go after its own Spanish garrisons and

rebellious cities He sent out a public letter, pleading with the factions

to unite against Spain because "our country is America."38

But he was only partially successful in stopping the civil war and when a

large Spanish army arrived from Venezuela in May, Bolivar sailed for

Jamaica with most of his officers.39

There, the

prolific Bolivar wrote his most famous document, Letter from Jamaica,

in which he declared, "A people that love freedom will in the end be

free." He foresaw a great federation of Hispanic American republics

which would deserve the same respect as European nations.40

A man of great

charm who could size up the people he met instantly, the indefatigable

Bolivar set out to persuade the world to back his vision yet again. He was

said to speak so eloquently on the spur of the moment that his speeches

could be printed without editing. He answered every letter written to him,

sometimes dictating to three secretaries at once.41

Bolivar's

pleas fell on deaf ears as far as governments went, with the exception of

Haiti, whose president agreed to provide money and equipment. In March

1816, the first expedition sailed with 250 men in seven ships, an absurd

force to engage the 10,000-strong royal army. They came across four

Spanish vessels and were able to board two. They landed the next day at

San Juan Griego and were warmly welcomed by the people. Another 300 joined

what was called the Liberating Army. But shortly thereafter they were

driven back and returned to Haiti for reprovisioning.42

When Bolivar

landed in Venezuela again in December 1816, he was 33 and would remain

there for the rest of his life. He had 500 men with him; a nearby fort had

1,500 of the enemy, never mind the 16,000 government soldiers in Caracas.43

Bolivar began

circulating proclamations, making up stories about supposed victories in

various areas of the country, building an image of himself everywhere and

invincible. In actuality, he operated mostly on the plains around the

Orinoco river in the interior, headquartered in remote Agostura.44

And Bolivar

was actually spending much of his time quelling efforts by subordinates to

usurp his command. Bolivar showed excellent political skills in

maneuvering around the many internal roadblocks, but finally felt

compelled to execute the leading conspirator, Manuel Piar, who was,

unfortunately, was also the republicans' best tactician.45

One man became

indispensable to Bolivar's new strategy: Antonio Jose Paez, seven years

his younger (who had an enormous bodyguard called the First Negro who had

an knife so large no one else could wield it). Paez had mastered the

supreme difficulties of guerrilla cavalry warfare in the tropics. Some of

the llaneros were so impressed by him that they changed sides. His

lightning attacks achieved the first victories against the powerful army

which had landed in 1815.46

Antonio Jose Páez at the battle of Las Queseras

del Medio

By May, the

2,000 republicans had achieved some significant victories. One incident

illustrated how much they thrived on boldness. With 15 of his officers on

a reconnaissance, Bolivar spotted a large number of Spanish soldiers lying

in wait to ambush him as he rounded a corner. He shouted for his men to

form up and prepare for an assault on the enemy position--as if his own

army were right behind. The Spaniards retreated.47

In January

1818, Bolivar's 3,000 soldiers marched 350 miles through a swampy region

to join Paez's 1,000 cavalry. Armed mostly with lances and bows and

arrows, they surprised one Spanish garrison after another. The commander

if all Spanish forces in Venezuela and New Granada, Pablo Morillo, barely

escaped.48.

But

inevitably, Spanish numbers and arms turned the tide prevail. Bolivar

retreated to El Semen with 2,000 men and while he was passing baggage over

a ravine on March 25, royal forces attacked. The rebels were exhausted and

Morillo killed half of them, capturing their materiel and papers, though

Bolivar escaped. The Spanish were sure that he was finished this time.49

But Bolivar

was discouraged by the lack of popular support, but he still had Paez's

2,100 horsemen. He immediately began rebuilding the infantry by recruiting

from convalescent hospitals and among teenage boys.50

Gradually,

though, he realized that the only way to achieve a level of

professionalism to match the enemy was to form a foreign legion. He began

raising money and his agents found great interest among the 30,000

recently discharged soldiers of the British army. The weather and the

inability of the rebel army to meet payroll was discouraging to the

mercenaries, but they adapted to conditions and became committed to the

cause. Of the nearly 6000 who joined, 220 drowned on the way over, some

deserted, and most were died from disease or in battle: only a few hundred

survived the war.51

In February

1819, a republican congress was convened to draw up a constitution for the

Third Republic.52

Map of Columbia, Published 1844

Meantime,

guerrilla warfare was being successfully waged by Paez's cavalry. In one

encounter, they lured the Spanish into a trap. The Venezuelans lost six,

the Spanish 400. The Spanish withdrew from the region after losing half

their 7,000 troops.53

Bolivar began

to conceive one of the most audacious military campaigns in history. He

had been operating on the eastern part of the Plains of Casanare. On the

western plains up against the Andes, Francisco de Paula Santander was

conducting a guerrilla campaign the Spanish found impossible to suppress.

During the rainy season when the plains were a virtual swamp, the royalist

troops withdrew and in April, Santander sent a message to Bolivar that the

area was free of the enemy.54

Bolivar knew

that the Andes were considered impassable during winter (in the southern

hemisphere) and that the Spanish guarded the frontier of New Granada on

the other side very lightly. He called a war council of his generals, all

of them under 40, in a hut without furniture; they sat on the bleached

skulls of oxen to discuss his idea on May 23.55

Hannibal had

spent years preparing for his epic trek through the Alps, as had San

Martin of Argentina when he made his own climb over the Andes, both with

seasoned soldiers. But within a week of making plans, Venezuela's 2,500

ragtag rebels set out to for the foot of the mountains.56 First,

though, they had to cross 10 swollen rivers, as well as move through

flooded plains with water often waist-deep, with the torrential rain

constant. Half the cattle brought along for food drowned. Bolivar

continually moved up and down his lines to exhort his men forward.57

On June 25,

they began the ascent into the mountains. The army consisted mostly

of men from the plains and Britain and Ireland, none of them prepared for

what they were about to face.58 The higher they went, the colder it

became. By the time they were at 18,000 feet, the horses and cattle had

died in the frozen wasteland.59 The half-naked men who had no wood

for fire most of the time, took to flogging each other to keep circulation

going.60 Nearly 1,000 men died along the way.61

Those who made

it to the other side of the range were half-starved and had dropped their

weapons along the way, but found a population eager to resupply them.62

After Bolivar's men had a few skirmishes with Spanish government outposts,

word reach the regional commander, who prepared to meet the rebels in a

well-defended position with 3,000 soldiers on July 24 at Pantano de

Vargas. After the revolutionaries' cavalry managed to charge in the steep

terrain and the foreign legion seemed to cinch a victory with a bayonet

assault, the Spanish pushed them back. It was a stalemate, but the

commander sent a report to the viceroy: "The annihilation of the

republicans appeared inevitable. But despair gave them courage. Our

infantry could not resist them."63

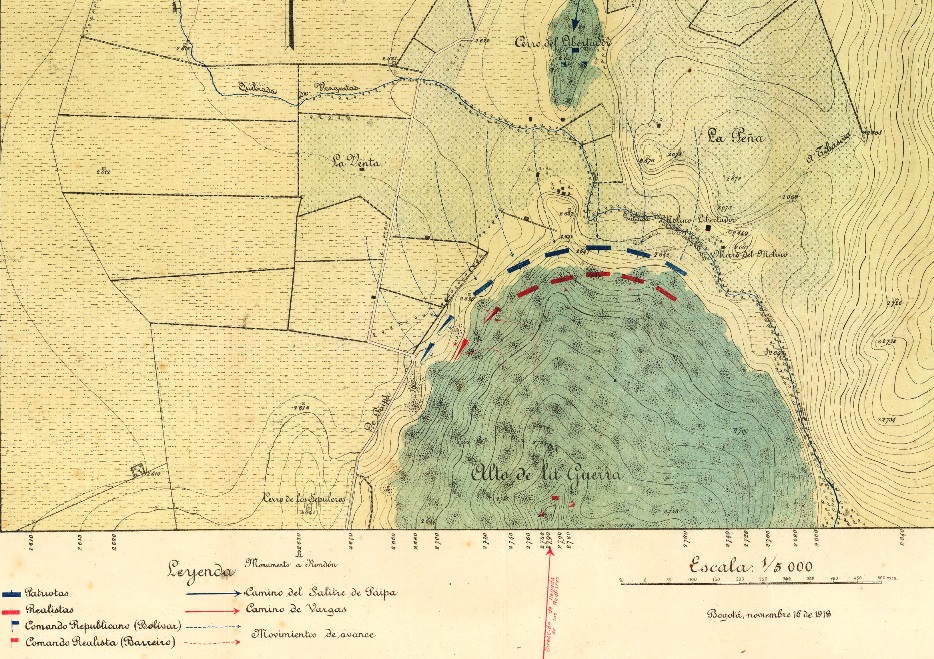

Battle of Pantano de Vargas

The Spanish

retreated and the patriots pursued. At Boyaca, on August 7, the rebels

prevented the royalists from crossing a bridge that would have allowed

them to reach the garrison at Bogata. In a two-hour clash, they captured

half of the 3,000 Spanish troops, the rest having been killed or fled the

battlefield.64 It was the turning point for the independence

movement in South America. The Spanish began to evacuate New Granada and

word spread like wildfire that the empire was coming to an end. Desertions

from the royal army increased and formerly neutral citizens began actively

supporting Bolivar.65

In December,

the underground legislature of Venezuela assembled and declared its

country and New Granada united as the Republic of Colombia (which included

what is now Ecuador). Bolivar was made president and military dictator.66

Political

events in Spain provided impetus for negotiations with the republicans

throughout 1820, but skirmishes continued.67 Bolivar and Morillo,

the Spanish commander, met in November and signed an armistice.68

In the following months, the patriots built up their army and made plans

for a campaign in the event a final agreement should not be worked out.

The conflict resumed in April 1821.69

On June 24,

the Spanish general La Torre brought 5,000 troops to Carabobo to block

both passes that could allow the rebels to move towards Caracas. He made

some decisive mistakes in position: a weak right flank, no sharpshooters

at the edges, and cavalry too far to the rear to be brought up in a timely

manner.

Bolivar, with

a total of 6,500 men, sent Paez with cavalry and infantry, including the

British battalion, around to the enemy's right rear, but while cutting

through the heavy bushes, that they were spotted. The Spanish reinforced

their right and concentrated fire on Paez's troops, repelling the initial

attack, which required the patriots to climb across steep ravines. But

when the overconfident Spanish broke out and chased them, the royalists

ran smack into the British veterans of the Napoleonic wars who cut them to

pieces with disciplined heavy fire at close range. Running out of

ammunition, the British charged with bayonets and the Spanish right

collapsed.

The main

forces of both sides had not yet engaged, but when Bolivar saw the outcome

on the right, he ordered a full attack. One-third of the Spanish troops

were captured and as many were killed or wounded.70

The region

between Cali (Colombia) and Guayaquil (Ecuador) remained a Spanish

stronghold after the victory at Carabobo. Bolivar had sent General Antonio

Jose Sucre south to aid the local revolutionaries and he had achieved some

success. In March 1822, Bolivar set out with 3,000 soldiers, but one third

of them perished from exposure or harassment from loyalist guerrillas.71

On April 7, he

came up against 1,800 Spanish troops in a seemingly impregnable position

in thick woods at Bombana. Bolivar ordered an attack on the right at night

under a full moon, losing a third of his 2,000 men under withering fire.72

But over the

next six weeks while the Spanish were concentrating on resisting Bolivar,

his right-hand, Antonio Jose Sucre, had gone around them, defeated

royalist troops positioned near Quito, the capital of Ecuador, and taken

it. From that base, he was able to mop of Spanish forces and Bolivar went

on to Guayaquil.73

Forces under

the generalship of Jose de San Martin, a 20-year veteran of service to the

crown, and Bernardo O'Higgins, son of an Irishman who had become viceroy

of Peru, had ended colonialism in Chile and Argentina. Between their

armies and Bolivar's troops lay Peru, with 19,000 Spanish troops, the last

of the empire. San Martin was well-provisioned and well-armed when he

marched over the Andes with 4,500 veterans to take Lima in June 1821.

However, had not been able to push further inland.74

On July

26, 1822, San Martin and Bolivar met in Guayaquil to see how they could

work together. There is no record of the meeting, but they didn't seem to

get along well personally and had different visions for the continent. San

Martin was so discouraged by Bolivar's impassioned insistence that his

views would prevail that he retired immediately to France. Peru was left

in Bolivar's hands.75

Meeting between Bolivar and San Martin

In June 1824,

Bolivar assembled an army of 9,000 in Peru to move 600 miles over the

Andes to the high plateau. Inadequately clothed, suffering from

sun-blindness, lack of oxygen, and the hazards of the dizzying precipces,

they climbed to 12,000 feet. One English general, a long-time veteran in

Europe, described it as the most difficult military operation he had ever

undertaken.76

At the top,

Bolivar reviewed his troops and told them, "Soldiers, you are about

to finish the greatest undertaking Heaven has confided to men--that of

saving an entire world from salvery!"77

On August 6,

Bolivar reached the heights above the Plains of Junin. Below, he spotted

part of the Spanish army moving across the plains. Bolivar sent 900 of his

horsemen to attack the 2,000 royal cavalry at their rear. The engagement

lasted 45 minutes, no shot was fired during the clash of lances and

swords. The patriots lost 120 men, the Spanish, who retreated in wild

disorder, 400. It was to be the last battle Bolivar would personally lead

against the king's men.78

Bolivar

stepped down to attend to political matters and put nearly 5,780 soldiers

under the command of Sucre. The Peruvian viceroy, La Serna, took 9,300

troops and began to pursue Sucre's forces. A cat and mouse game ensued

through country crossed by steep ravines and deep rivers. Bolivar wrote

Sucre that, "The axiom of Marshal of Saxony is being fulfilled. Feet

spared Peru; feet saved Peru; and feet will again cause Peru to be lost.

Fixed ideas always avenge themselves."79

The Spanish

finally trapped Sucre's army in the valley of Ayacucho on December 9. The

republicans had only one 4-pounder gun, opposed to the crown force's 24

artillery pieces. As the Spanish marched down on the republicans, Sucre

rode along his lines, shouting, "Upon your efforts depend the fate of

South America." Knowing that some of La Serna's subordinates

perpetuated massacres of surrendered troops, the rebels knew it was a

fight to the finish. One of Sucre's lieutenants killed his horse,

explaining to his soldiers, "I have now no means of escape, so we

must fight it out together." The Spanish were startled by the

fierceness of the republican resistance and when the latter charged with

bayonets, the Spanish lost 2,000 men and 15 guns. La Serna was taken

prisoner and the commanding general surrendered.80

Sucre's report

to Bolivar announced, "The war is ended, and the liberation of Peru

completed."81

Mop-up

operations occupied 1825 and in the same year the people of upper Peru

deciding to form a separate nation, which they named Bolivia in Bolivar's

honor. He wrote its constitution and accepted the position of lifetime

president.82

The fight for

the independence of Venezuela, Columbia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, and

Panama (a department of Colombia) had involved 696 battles, with an

average of 1,400 soldiers per engagement, counting both sides together.83

Bolivar

received a letter from the then-old Marquis de Lafayette on behalf of the

family of George Washington, along with a gold medallion coined after the

capitulation at Yorktown. It read, "The second Washington of the New

World." Bolivar was deeply moved.84

Simon Bolivar

began vigorously rebuilding and administering the devastated new states.

He was at the height of his power when he convened a congress of Latin

American republics in Panama in 1826. He envisioned a league of the

fledgling Central and South American nations, but he was far ahead of his

time.85

Soon

thereafter, fighting between the states, personality conflicts, and

resentment of his authoritarian ways caused his influence to wane. After

an assassination attempt and with failing health, Bolivar resigned all his

positions and died shortly thereafter on December 10, 1830.86

But to Latin

Americans, Bolivar remains immortal, one of the greatest military leaders

in the history of the entire world.

SUGGESTED READING...

huascar.jpg" width="566" height="370">

huascar.jpg" width="566" height="370">

War Along the Pacific Coast.

First Britain. Then Chile. All challenged Peru's Ironclad

Warship Huascar.

It is a story of Bravery, Honour, Technology and Bird Droppings...

ENDNOTES

1. Gerhard

Masur, Simon Bolivar (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press,

1948), pp. 11-25. The Encyclopedia Britannica calls Masur's volume the

"best biography of Bolivar in the English language." It should

be available in any good library. Although I consulted half a dozen other

books, all references are to Masur unless otherwise noted.

2. 28

3. 31, 33

4. 37

5. 39

6. 41-43

7. 68

8. 77, 80

9. 79

10. 80

11. 86-89

12. 89

13. 233

14. 92

15. 90-91

16. Lauran Paine,

Bolivar the Liberator (New York: Roy Publishers,

1970), pp. 48-50.

17. 100-101

18. 105

19. 107

20. 114-115

21. 116-117

22. 119

23. 122-125

24. 128

25. 132, 138; Paine 72

26. 144, 148-149; Paine 77

27. Paine 81-86

28. 153

29. 154

30. 159; Paine 81-86

31. 158-159

32. Paine 84-85

33. 160

34. 161

35. 162-3

36. 172

37. Paine 90

38. 165-166

39. 171-172

40. 185

41. 178-179

42. 195-203; Paine 101

43. Paine 101

44. 207

45. 206-219

46. 220-0223

47. 210

48. 231-233

49. F. Loraine Petre,

Simon Bolivar: "El Libertador" (New

York: Best Books, 1924) p. 204.

50. 236

51. 238; Petre vii, 213

52. 245

53. 258

54. 261

55. 263

56. 273; Petre 224

57. 265

58. 266

59. 268; Paine 124, 126; Petre 441

60. 268

61. Bill Boyd,

Bolivar: Liberator of a Continent (New York:S.P.I.

Books,1998), p.93.

62. Petre 441

63. 269-270

64. 271-272

65. 274-277; Paine 129

66. 283-284

67. 292-293

68. 297

69. 304

70. Paine 141-142

71. 323

72. 323-324

73. 325, 328

74. 33-336

75. 337-343

76. 374

77. 374

78. 374-375; Paine 12

79. 377-378

80. 378-379; Paine 172

81. Petre 340

82. 394

83. Boyd viii (re Panama, usually overlooked); the number of battles and

average number of combatants is from Petre 397

84. 399

85. 411

86. 487