|

"Ramming

Speed!"

Naval

Battles of the Ironclad Emperor of the Pacific

A Story of

bravery, honour, technology and bird droppings

Named

after an Incan Emperor, the Peruvian Ironclad Huascar rams the

Chilean Corvette, Esmeralda at the Battle of Iquique (Thomas Somerscales)

Naval warfare

had shifted for good: wooden ships and iron men had been replaced

with iron ships and nerves of steel. The development of

steam-powered armoured warships had forever changed how combatants

engaged at sea. Steam power offered speed and maneuverability.

Armour provided protection for close-quartered movements and allowed

the vessel to endure raking fire that would have destroyed a wooden

ship. In short, an ironclad ship could get up close and personal.

Interestingly, this technological leap also heralded the re-birth of

the forgotten naval ram.

Ancient Greek and Persian ships using rams

decorated as ravens and wild boars.

Introduced by the Greeks in the 8th Century BC, the

wooden ram at the bow of a vessel was used to sink an enemy ship.

The ram was useless during the ensuing age of sail and artillery.

Indeed, to point your bow at another vessel meant certain death as

your ship was raked with cannon fire from enemy broadsides. For over

two centuries, naval fleet battles essentially consisted in two

lines of ships blasting away at each other, waiting for the wind to

offer advantage to either side. But on March 8, 1862, everything

changed.

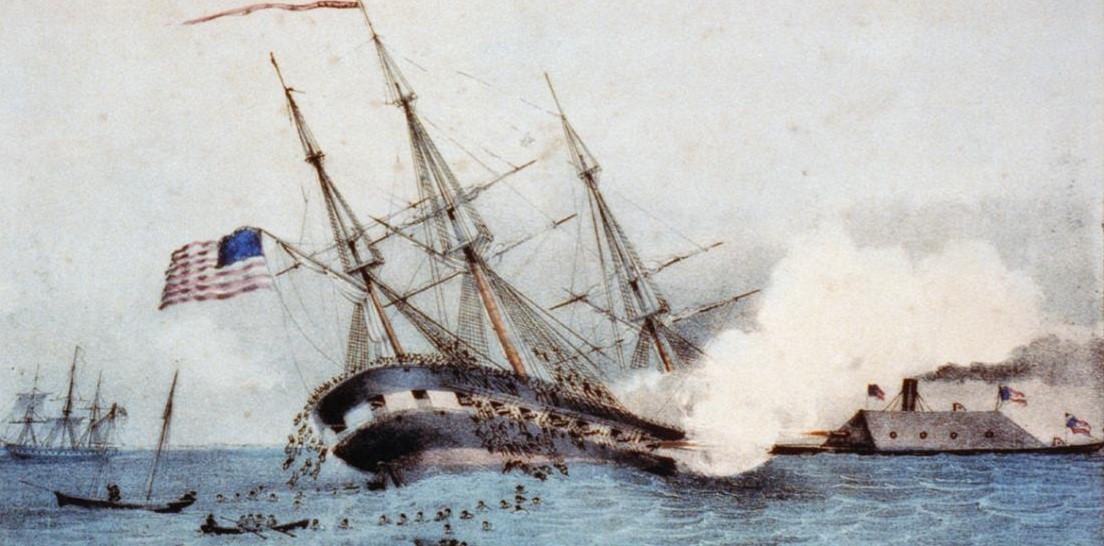

As the American Civil War raged on, the Confederate ship Virginia

quietly slipped out of harbour. Covered in iron and sporting a ram,

the Virginia put the theories of contemporary naval

tacticians to the test. The USS Cumberland, a 38-gun wooden

enemy frigate, was rammed and sunk at surprising speed.

Unfortunately for the Confederate crew, their poorly-secured ram

went down with the enemy ship. Still, by the end of the day, the

Virginia had beached two other enemy ships with its artillery,

while suffering minimal damage.

Ironclad CSS Virginia rams and

sinks the USS Cumberland

Sunrise brought the Union’s response: the ironclad USS

Monitor. The

Virginia answered the call and the world’s first encounter between

ironclads began. The two ships fired at each other relentlessly over four

hours, continually bouncing iron shot off the other’s haul, like armoured

knights smashing each other with maces. A hull breach was not likely for

either ship: stalemate. This thunderous artillery duo also sounded a death

knell for the wooden warship. It was only a matter of time before ironclads

were designed to be sea worthy and ventured off the coastline.

The CSS Virginia and USS Monitor bounce rounds off each other’s armour. A

frustrated Confederate officer commanding a gun said

he did the same damage to the Monitor “by snapping his fingers at her every

two and half minutes.”

The pings of cannon shot hitting armour that day reverberated around

the world as navies scrambled to adjust to this new tactical

reality. Steam-powered wooden ships were faster, but it was certain

death if they allowed an ironclad to close in on them. Soon, mixed

fleets of ironclad frigates and wooden ships challenged each other

on the open sea.

Battle of Lissa, 1866. Italian Ironclad sinks. Marines on deck give a

parting volley of defiance at the Austrian ironclad frigate that sunk their

ship.

At war, the Italian and Austrian fleets met in combat off the Island

of Lissa on July 20, 1866. Over forty vessels engaged. The Italian

ironclads identified the towering Austrian three-decker, 90-gun

wooden ship Kaiser (German for “emperor”) as the enemy’s flag

ship and swarmed it. Lacking maneuverability because of its size,

the Kaiser was soon rammed and forced from the battle.

Ironclads had successfully engaged in open sea.

Like the great powers, smaller nations embraced the ironclad’s

future. Peru was one country to join the movement out of

necessity. Spain began to reassert itself over its former South

American colonies. Spain’s dispute with Peru? Strangely, it was

bird dung. Millions of tons of bird droppings, called guano. High in

nitrates, guano was a much-sought-after fertilizer, similar to

potash today. There was a fortune in bird droppings to be had on the

Peruvian Chincha Islands and Spain wanted it.

The Great Guano Heap, or a mountain of bird crap that started a war.

After trumping up a collection of excuses, Spain sent a fleet to

occupy the islands in 1864. Accompanying the Spanish naval

expedition was the ironclad frigate Numancia. After the war

for the Chincha Islands, the Numancia would become the first

ironclad to circumnavigate the globe.

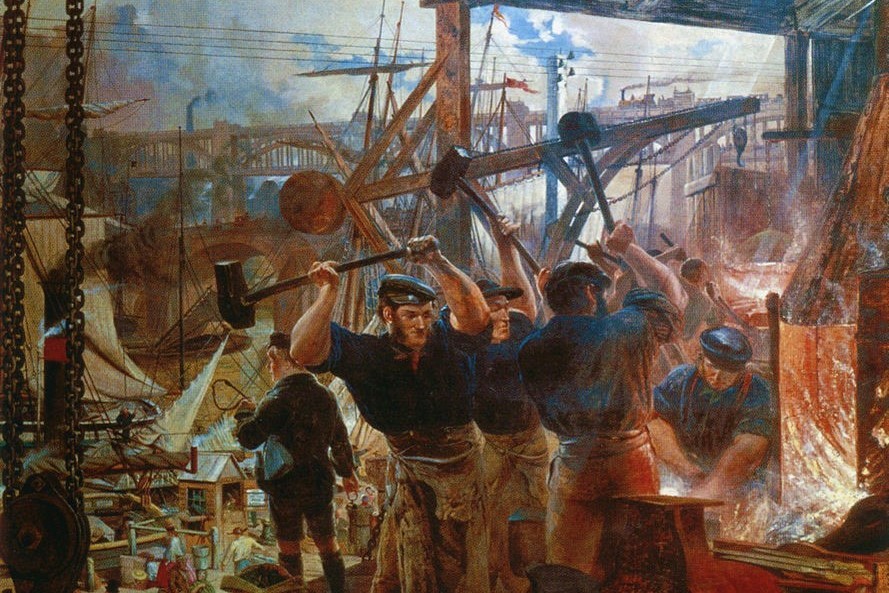

British

Shipyard workers in Iron and Coal by William Bell Scott,

1860.

Hopelessly outgunned by the Spanish fleet, Peru turned to British

shipbuilders for a solution. Peru spent what would today be the equivalent

of tens of millions of dollars to commission the building of two ironclads:

a frigate and a turret ship. The latter ship’s design had a turret similar

to the USS Monitor but mounted on an ocean-worthy ironclad ship. The

turret housed British state-of-the-art artillery: two Armstrong guns capable

of firing 300lb rounds. Delighted at the strength of their turret ironclad,

the Peruvians named it Huascar, after its most famous Incan emperor,

and made it their flagship.

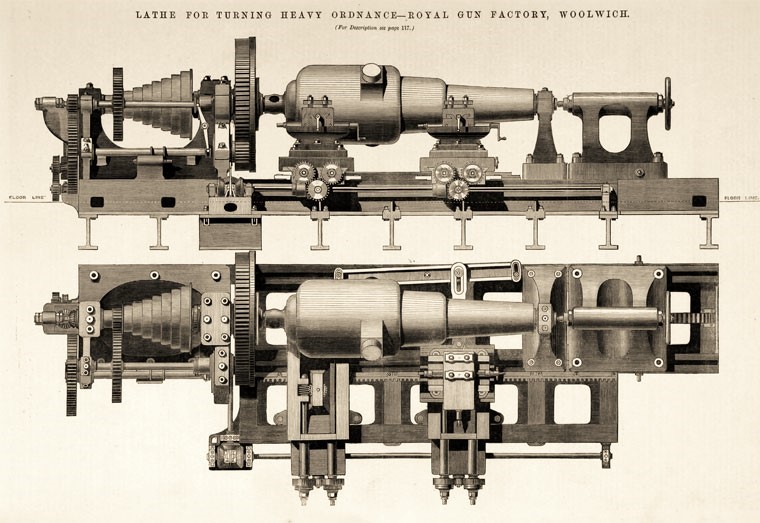

Barrel of a heavy

Armstrong Gun being lathed in England. 1867. The Huascar had Armstrong

Guns with 10-inch muzzles.

Completed in January 1866, the Peruvian ironclads set sail for their

new home. After a number of delays, the Huascar arrived in

the war zone in June. Meanwhile, having been denied access to coal

along the South American coast, the Spanish broke off their

half-hearted war with Peru and set sail for the Philippines. Peru

and Chile contemplated an attack on the Spanish in the Philippines

but the idea was ultimately abandoned. Still “the Emperor”

Huascar had arrived in the Pacific and ironically, its first

real fight would be against its creators.

In 1877 political intrigue brought Peru to the brink of civil war.

Rebels wishing to overthrow the country’s president daringly seized

control of the Huascar while at dock on May 6 and put it to

sea with piracy in mind. Their strategy was to destabilize Peru’s

trade by commandeering the ship and showing the weakness of their

reigning president. In its brief time as pirate, the Huascar

interfered with a British mail steam ship and stole coal from

another British vessel. It was unacceptable to Great Britain that a

small but well-armed rogue ironclad was preying on Pacific coast

merchant vessels and the Royal Navy responded.

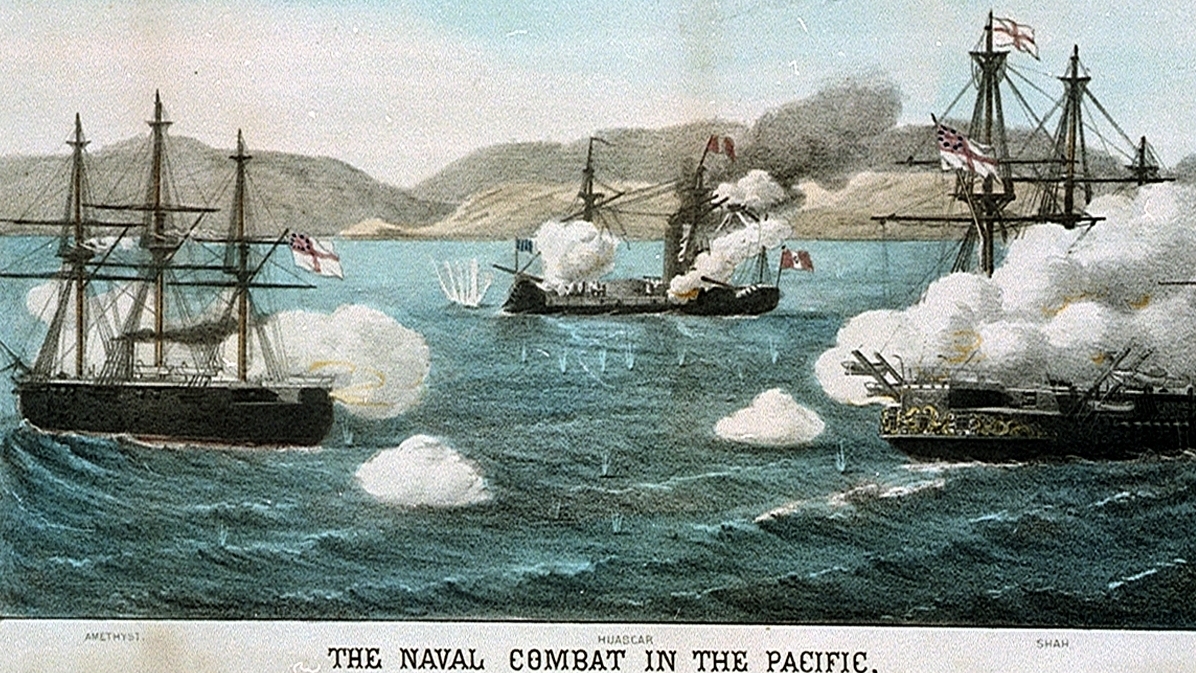

HMS Shah

and HMS Amethyst engage the Peruvian Rebel Ironclad Turret

Ram Huascar.

On May 29, two wooden British frigates, HMS Shah and HMS

Amethyst confronted the Huascar off the southern coast of

Peru near the town of Ilo. The rebels were surprised to see British

ships and even more astounded when they demanded the Huascar’s

surrender. The Huascar’s crew felt their infractions against

British property verged on trivial. Sensitive to any imperial

interference, Peruvian rebels were insulted by the Royal Navy’s

intrusion into what they saw as an internal affair. The Huascar

refused to surrender and the British open fired.

However, the British had built the Huascar well and the guns

of the Royal Navy ships could not damage it. To the relief of the

British crews, the Peruvian rebels were terrible gunners and could

not bring their lethal artillery to bear. Superior Royal Navy

training also allowed the British frigates to maneuver around the

Huascar’s attempts at ramming. After three hours of fighting,

the small and rapid Huascar retreated, but the British had

another card to play.

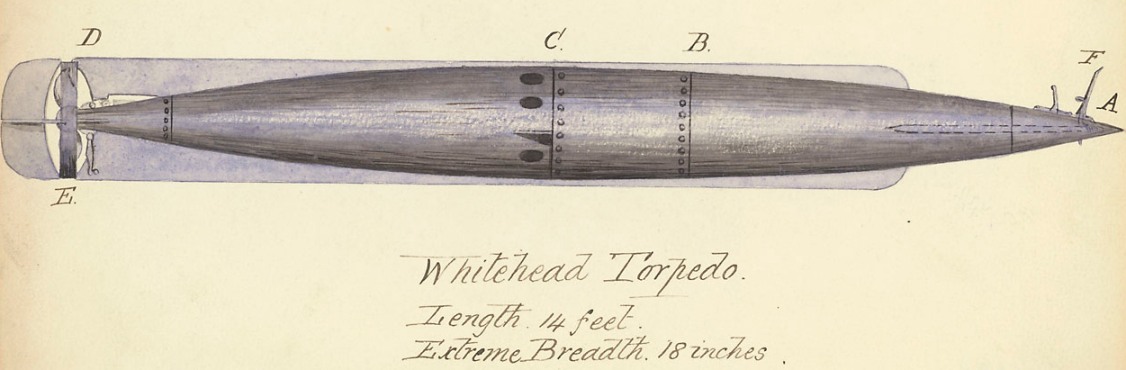

Whitehead

Torpedo, 1877. A.-B. The Charge Chamber of sheet iron. B.-C.

Adjustment Chamber of sheet iron.

C.-D. Air chamber and engine room of steel. E. Propeller F.

Vertical exploding Lever.

The British HMS Shah was fitted with a new weapon, never

before used in combat by the Royal Navy: The Whitehead Torpedo. This

self-propelled “locomotive” torpedo was sighted and launched at the

fleeing Huascar. In the end, the speed of the Peruvian

ironclad and its distance from the Shah outmatched the

British torpedo. The Royal Navy’s first battle in history with an

ironclad ended. Soon after, the rebels surrendered the Huascar

back to the Peruvian Navy. As a strange twist in the story, even

though the British had fought the rebels, the Peruvian government

lodged a formal diplomatic complaint against Great Britain for their

attack on the Huascar. Clearly Peru cherished both its

independence and the Huascar. But another war lurked on

the horizon, and Peru would need its little ironclad Emperor.

CONTINUE TO THE EXCITING FINAL PART

>>>>>>

|

Author

Robert Henderson enjoys unearthing and

telling stories of military valour, heritage, and sacrifice

from across the globe. Lest we forget.

|

|