|

"Come on you brave Yank, come

on"

Texan respect for an enemy hero at the Siege of Vicksburg in 1863

The Siege of Vicksburg, 1863 (pub. 1888)

LIKE MANY YOUNG MEN, THOMAS HIGGINS WAS DRAWN TO THE ROMANTICISM OF MARCHING

OFF TO WAR.

Born in Huntingdon, Quebec, Thomas had crossed the border from Canada in

1862 and joined the Union Army in Barry, Illinois.

He wasn't alone. Though it was illegal under the Foreign Enlistment Act of

1819 for British subjects to enlist in foreign armies, over 40,000 Canadians

did so like Thomas.

As a private in Company D of the 99th Illinois

Regiment, Thomas found himself at the walls of Vicksburg, Mississippi on May

18, 1863. Commanding the Union Army of the Tennessee was Ulysses S.

Grant.

Grant hoped for a quick victory by storming Vicksburg's defences and

overwhelming the Confederate defenders who were outnumbered three to one.

However the first assault on May 19 proved a demoralizing failure with over

a thousand casualties.

Morale improved as the Union Army was

provisioned and on the night of May 21 troops enjoyed a princely meal of

hardtack (dry ship's biscuit), beans and coffee. On the following

morning, after heavily shelling Confederate positions, Grant ordered a new

assault. While passing his troops before the attack on May 22, Grant

received a spirited chant from the Union soldiers of "Hardtack! Hardtack!"

The 99th Illinois Infantry was chosen as one of the lead units. The

regiment's color bearer had been wounded a few days before. On the morning

of the assault, regiment's acting commanding officer recounted: "Private

Thomas H. Higgins, a big, strong, athletic Irishman. solicited the privilege

of carrying the flag for the day. I gave him permission and handed over the

standard to him, telling him not to stop until he got into the Confederate

works."

Private Charles H. Ruff

of the 2nd Texas Infantry Regiment (Library of Congress)

The target the

99th Illinois was tasked to capture was a crescent-shaped fortification

later called the 2nd Texas Lunette. Defending this key section of

defence works was the 2nd Texas Infantry. Mostly made up of men from

Houston and Galveston, the 2nd Texas were not unfamiliar with the risks of

attacking a fortified enemy position and the dangers to those who carried a

regiment's color. At the Second Battle of Corinth the previous

October, the 2nd Texas had fiercely fought to capture a battery redoubt.

At times fighting hand-to-hand, the 2nd Texas that day had five successive

color bearers fall in the action. The last to die carrying the 2nd

Texas color was their Colonel, William P. Rogers. Seeing his

regiment's falling for the fourth time, Rogers had seized them, jumped a

five-foot ditch, abandoned his dying horse and continued the assault.

He was killed soon after by canister shot.

. .

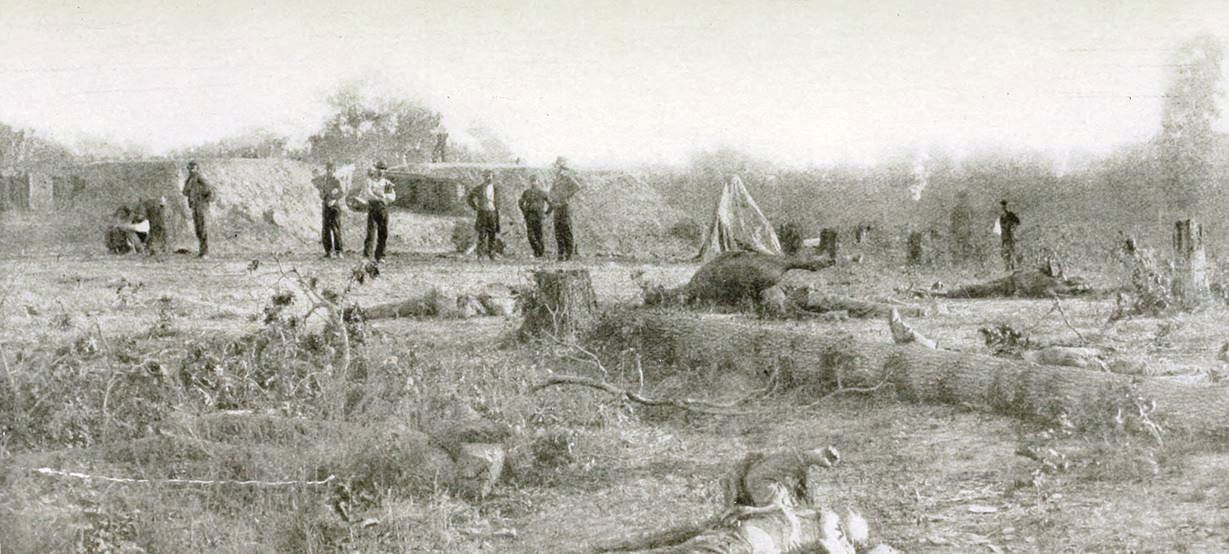

Outside the Corinth Battery redoubt after the failed assault by the 2nd

Texas Infantry.

Visible are the bodies of Colonel Rogers (left background) and his horse.

That morning of May 22 at Vicksburg, the 2nd

Texas found themselves now the defenders. Retribution was at hand.

For two hours Union artillery relentlessly

pounded the earthen fortifications manned by the 2nd Texas: "the very earth

rocked and pulsated like a thing of life." When the bombardment

ceased, the 99th Illinois appeared in column with the union standard flying

in the hands of Thomas. The union assault force was "about 100 yards in

front of the breast works, and, as line after line of blue came in sight

over the hill, it presented the grandest spectacle the eye of a soldier ever

beheld", recounted Charles Evans of the 2nd Texas.

However the Texans were ready. Along with

their Springfield rifles, each man had five additional smooth-bore muskets,

loaded with buck and ball. In essence, they could deliver six times the

firepower the Union troops were expecting. The Texans held their fire

until the 99th Illinois Infantry were within fifty paces of the earthworks

then "the order to fire ran along the trenches, and was responded to as from

one gun. As fast as practiced hands could gather them up, one after another,

the muskets were brought to bear. The blue lines vanished amid fearful

slaughter." Of the three hundred of the 99th Illinois who marched

forward, a third fell killed or wounded. But Thomas was still alive

and unhurt.

Evans of 2nd Texas remembered the surprising

event that happened next:

"As the smoke was slightly lifted by the

gentle May breeze, one lone soldier advanced, bravely bearing the

flag towards the breastworks. At least a hundred men took

deliberate aim at him, and fired at point-blank range, but he never

faltered. Stumbling over the bodies of his fallen comrades, he

continued to advance. Suddenly, as if with one impulse, every

Confederate soldier with sight of the Union color bearer seemed to

be seized with the idea that the man ought not to be shot down like

a dog. A hundred men dropped their guns at the same time; each

of them seized his nearest neighbour by the arm and yelled to him:

Don't shoot at that man again. He is too brave to be killed

that way, when he instantly discovered that this neighbour was

yelling the same thing at him. As soon as they all understood

one another, a hundred old hats and caps went up into the air, their

wearers yelling at the top of their voices: 'Come on, you brave

Yank, come on.'"

'Come on, you

brave Yank, come on.' Higgins is cheered on by the Texans. (pub. 1901)

Thomas Higgins followed his commander's orders

to the letter that day

"not to stop until he got into the Confederate works."

To the sounds of cheers of his enemy, Thomas reached the base of the

breastworks and the flag on the parapet. Surprisingly there was not a

scratch on him. After being taken prisoner, Thomas was congratulated by the

2nd Texas for his miraculous escape from death. His feat

resonated with the Texans whom themselves had lost five color bearers

at Corinth in 1862. A few days later Thomas was paroled and eventually

exchanged. He ended the war with his regiment. raising to the rank of

sergeant.

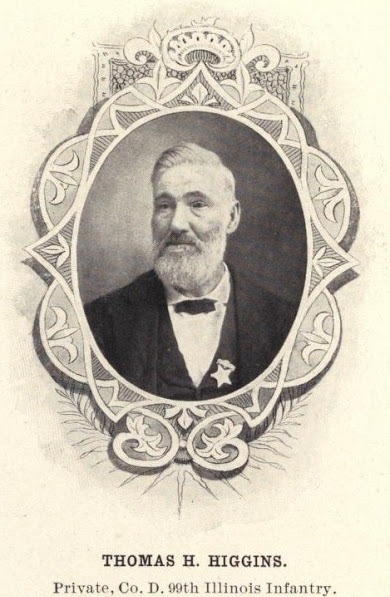

On April 1, 1898 Thomas Higgins got a surprise.

He was awarded the United States highest personal military decoration: the

Medal of Honor. But who recommended him for it? The answer was

not his comrades but his former enemies: the Texan Confederates that had

cheered him on that day.

Photo of Thomas Higgins in 1998.

A Canadian in the Union Army cheered

by Texan Confederates. He was a lucky one.

Over 7,000 Canadians died in the war,

mostly on the Union side.

|

Author Robert Henderson enjoys unearthing and

telling stories of military valour, heritage, and sacrifice

from across the globe. Lest we forget.

|

|